Exiled from the Heart: coming home to myself

- Marianne Musgrove

- Oct 16, 2019

- 3 min read

There are three things I know about my paternal grandmother: She was born in 1891 in a small village in Holland. During the Second World War, when food was scarce, she would feed her family on tulip bulb soup. When a Jew turned up on her doorstep seeking shelter, she hid him in the glass house out back while German soldiers supped inside her home.

A few years ago, I came across her identity card in a stack of my dad’s papers (pictured). It was both fascinating and chilling to see this tangible piece of history from the Nazi era. Adriana van Vliet had to carry this card with her at all times. As such, for the duration of the German occupation of The Netherlands, she was subject to a curfew, and there were places she was forbidden to go. While not technically a refugee, she was, in effect, an exile in her own country.

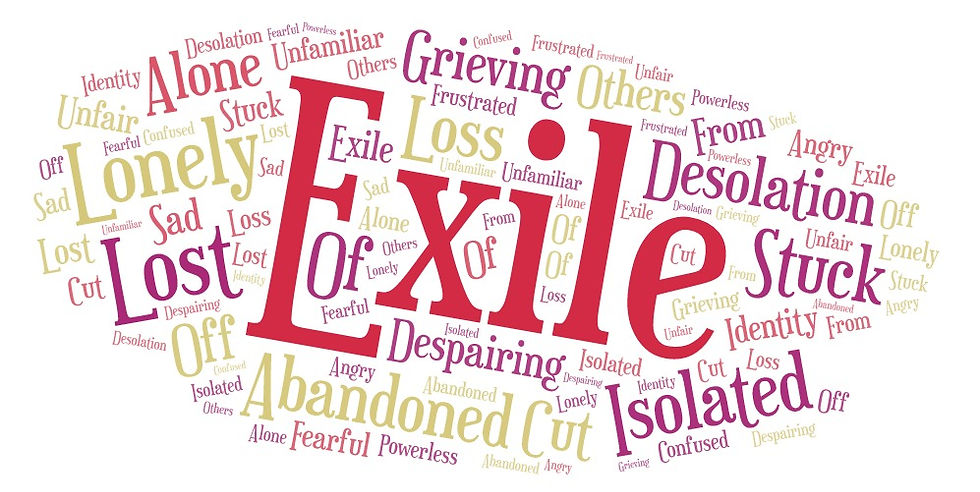

I shared this story in church last Sunday and, in response, we brainstormed a list of words that expressed what it would feel like to live in exile.

We did the same with the word, ‘home’.

It struck me that the words we chose to describe exile could also be used to describe a state of separation from God. Similarly, the words used to describe home captured the essence of being one with God.

We all experience exile in one way or another. It’s part of the human experience. Perhaps someone is shunned by family or community for their beliefs, their sexuality or because they’ve breached social conventions. A person can even be exiled from themselves, shut off from their own emotions, shut off from love. Given exile is a universal experience, how can we return to God, our true home?

The Judeans in Exile

Jeremiah 29:1,4-7 explores the story of the ambitious Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar who raids Judea and orders the kidnapping of thousands of Judeans. Once captive, these people long for nothing more than to return home. When the prophet Jeremiah hears of their plight, he sends them a letter.

It is not what they expected.

Instead of telling them what they want to hear (that God has promised to bring them home imminently), he tells them to build houses and plant gardens in their place of exile. What’s more, he instructs them to have children and for their children to have children. Clearly, he foresees that their exile will be of long duration, and indeed this is exactly what happens – the Judeans were ultimately held captive for 70 years. Yet despite this long sentence, he encourages them to live an abundant life right where they are.

What does this story say to us about how we approach our feelings of exile?

My Own Experience of Exile

As a writer, I have periods when my writing flows well and times when I’ve been stricken with writer’s block. When the writing is going well, the ideas come to me effortlessly, I lose track of time, and I feel a sense of joy as the words pour forth onto the page. I’m living out my calling and I feel at home.

But when my writing isn’t going well, I am beyond frustrated. Fears circle me like vultures. ‘My writing isn’t good enough.’ ‘I’m not good enough.’ ‘It’s hopeless. I’ll never write again.’ As the negative thoughts and emotions multiply, I feel exiled from my calling, and cut off from the joy it usually brings me.

In response, I tend to fall back on one of two responses:

1. I dwell on these thoughts and feelings and get mired in fear and negativity; or

2. I avoid the uncomfortable feelings by walking away and procrastinating.

For a long time, it’s been apparent to me that neither of these approaches works. Thankfully, Jeremiah offers us an alternative.

Build a home. Plant a garden. Multiply.

In other words, put down roots right in the midst of the discomfort and accept the experience for what it is. By neither dwelling on negative thoughts and feelings nor avoiding them, but instead mindfully watching them without judgement, they pass through me remarkably quickly, leaving me feeling calm and centred.

So perhaps the way out of exile isn’t to escape it but to encounter it – an act of radical acceptance of What Is. And when we invite God to be with us through this process, the very act of planting a garden in the midst of exile paradoxically becomes the path home.

Thanks, Carolyn! Stoic is an interesting choice of word as many in my family use that word to describes ourselves :)

This is also a very Stoic look at the issues you have written about, and I can see the worth of what you have written here. Thank you!